My Post-Army Vietnam YearsBy Beryl DarrahShortly

after arriving home, it was time to start back to school to earn

the credits necessary to be certified as an elementary school

teacher in the state of Kansas. It was also time to realize that

just having arrived from a war in Vietnam was no asset---or

drawback either---in society in g Completing the necessary hours certification was no problem. I ended up dropping an art class taught by a somewhat less than masculine teacher. I clashed with the young, inexperienced P.E. methods teacher and ended up with a C. But the rest of it went by rather smoothly. Boring, basically useless, but smoothly. This was my first realization that people who teach other people to teach usually have never taught themselves, or, if they have, it was so long ago that what they teach is outdated, idealistic, theoretical, or utter nonsense and has little relation to what actually takes place inside a real classroom. But, having no other choice, I jumped through the hoops the best I could and ended up with my elementary teaching certificate. It

was while I was doing my student teaching in Nickerson, Kansas,

that the origins of my return to South Vietnam were born. I was

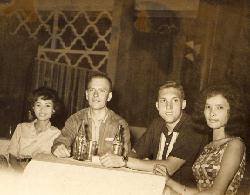

sitting in the back of the class trying to conc Earlier, when I was teaching at Prosperity School, I had been accepted by the Peace Corps. But I had already signed a contract---and the draft was not breathing so heavily down my neck at the time. Although I knew I was making a mistake, I turned them down (and ended up with a draft notice about a year later.). This time, I did not let the opportunity escape. I accepted the job offer and was soon on my way to Washington, D. C. to learn to teach English as a second language, and to study the Vietnamese language. For the next two months, I studied Vietnamese at the Foreign Service Institute in Arlington, Virginia, and studied how to teach English to Vietnamese at George Washington University. We were housed in a run down, drafty building (located near the World Health Organization building and also near the Department of State) that masqueraded as a hotel. Each morning my roommate, Robert Walker (I think that was his name.) and I would eat our breakfast in a nearby drugstore and then catch a bus to George Washington University. After eating lunch, we would catch another bus to the Foreign Service Institute where we would spend the remainder of the day studying Vietnamese, taught by the wives of Vietnamese military and diplomatic personnel. Week nights were pretty much drudgery, but on the weekends we were free to roam and explore. Of course, we had no automobile, so wherever we went, we either walked or went by public transportation. We actually saw a great deal of Washington. The White House, the Capitol Building, the Smithsonian, Arlington National Cemetery, Georgetown, the monuments, the famous government buildings. It was a great education as well as fun. Unfortunately I did not have a camera at the time---not even a cheap Brownie. So none of the sights that I saw were captured on film. A real pity. One morning I was walking by myself to the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, the church where Peter Marshall used to be the pastor. As I was walking past the White House, I happened to look up to see one of my former college professors walking toward me a few feet away. We were both rather startled, I think, but it was a pleasant chance meeting. On Friday nights, we would usually get dressed up and eat at a restaurant called the Black Angus. It was a fancy place which required advance reservations (as well as jacket and tie). We could easily save more than enough money from our daily living allowance to pay for the expensive food and service. Of course, we had to walk, but that did little to deter us or to dampen our spirits. One night we attended a performance of the Ringling Brothers Circus. I fell asleep shortly after the show started and didn’t wake up until it was over. I guess I am not a big circus fan. But mostly, at night, we studied Vietnamese in the basement of the State Department Building. When our training was finished, I couldn’t wait to leave for Vietnam. I persuaded them to let me go on ahead by myself and not wait for the regular departure date. It was exciting to be on the airplane headed back to Vietnam. After stops in Tokyo and Manila (or was it Taipei?), we landed in Saigon, and it felt like I was back in familiar surroundings. I checked into a downtown hotel for the night. It was a hotel that was under construction when I had left there a few months before. It looked like it was going to be a real luxury hotel. It turned out to be a dump. But at least it was a home base to anchor me while I spent the next couple days exploring and reacquainting myself with downtown Saigon. After a couple days, I took a taxi to the IVS headquarters, a couple of villas on the western outskirts of town on Le Van Duyet Street. When I walked in and introduced myself, they were rather shocked that I had come to Saigon by myself and had stayed in town by myself. Of course, what they didn’t know at the time was that I had already spent a year in Saigon and already knew my way around. However, I did move my belongings from the hotel to a dorm room at IVS. It wasn’t much to speak about---actually not much better than what I had experienced in the Army, except this time I was civilian and not a soldier. After a few days, the rest of the volunteer teachers whom I had known back in Washington D. C. came, and we spent a week or so in orientation meetings, studying Vietnamese, and sort of getting settled down. I was hoping very much that I would be sent to the Mei Kong Delta, for some reason. But instead I was assigned to teach English in Phan Rang, the capital of Ninh Tuan Province on the central coast of South Vietnam. Those

first days in Phan Rang are not very clear in my mind right now.

At the time I arrived, there was only one other guy assigned

there. His assignment was to help the area farmers do something

that I never quite figured out. His college degree was in poultry

science, and it would be an understatement to say that he knew a

lot about chickens. And in that little town chickens ran loose

everywhere. As we would walk around the town, chickens were a

common sight. To me a chicken is p Speaking of pigs. One day a commander from the 101st Airborne Division called to asked me to come out to the air base to see him. He wanted help disposing of the garbage from the dining halls (mess halls). He asked me is I could arrange for local farmers to pick up the garbage and feed it to their pigs and other animals. I made an appointment to see him one afternoon and drove out to the air base to meet him. He wasn’t there, so I left (much to the consternation of the clerk in his office.) He called again and made another appointment after apologizing for standing me up on the last one. He said that that he had been flying a mission (probably a training mission), and had arrived just a few minutes after I left. When I went to the air base the second time, he made an obvious point of telling me that he had cut short his flight in order to meet with me. At any rate, I was able to arrange for many of the area farmers to collect his garbage---which they did happily It would not be a surprise to me if they ate some of it themselves, as well as feed it to their pigs. It also wouldn’t surprise me if they sold much of it and made a huge profit on it---something the Vietnamese were not adverse to doing in those days. What did I get out of it (except for the satisfaction of doing my job, of course)? I got four boxes of military c-rations which became my meals for the next several weeks. The

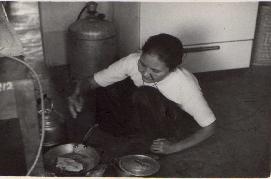

c-rations probably came at the right time, too. I had been taking

my meals from a local restaurant. I paid a flat weekly fee for the

meals which were very "local", very Vietnamese. They

consisted of rice, soup, fish and bread---and, oh yes, tea. After

a month of so of eating rice for every meal, breakfast, lunch and

supper, I was beginning to tire a bit of rice. In fact, there came

a Another part of the "cultural" adjustment in the early days was getting used to hearing the sound of mortar and rocket fire. The first night I heard mortar fire, I was scared to death. It all seemed so close, and so loud. I lay in my bed just waiting for one to come crashing through the roof of our house. Or for some Viet Cong soldiers to come bursting in to shoot me in my sleep (except I wasn’t sleeping). My roommate, on the other hand, was sound asleep, oblivious that anything was going on. I would learn in time that Ninh Tuan Province was probably the safest province in South Vietnam. It was the boyhood home of President Thieu, who was rumoured to have a relative (a brother, maybe?) who was a general in the Viet Cong army. At any rate, the sound of falling artillery became a familiar sound in the distance, and I, too, was eventually sleeping peacefully through the night. My

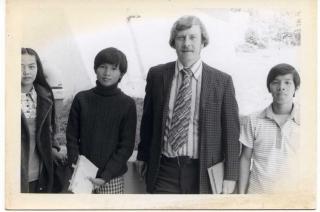

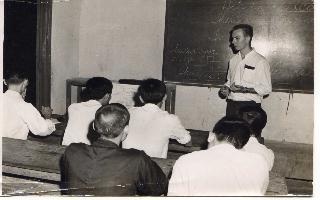

job in Phan Rang was to teach English in the local high schools.

It was more or less left up to My favorite place to teach soon became the Catholic High School, if for no other reason their discipline was far superior to the other schools. Let me interject here that all of the schools were built so that every classroom opened to the outside. There were covered walkways extending around the schools, somewhat like long porches. Students would leave one classroom and walk down the "sidewalk" to their next class. This eliminated the need for interior hallways, which would have been very hot and dark. Anyway, getting back to the Catholic High School. The principal of the school would constantly wander up and down these outside "corridors", always looking into the classrooms to see that was going on. If he happened to see a student misbehaving, he would swoop into the classroom, grab the misbehaving child be the back of the neck or the ears, drag him outside into the courtyard, and let him kneel in the gravel (in the hot sun) until he believed the offending kid had learned his lesson. And, heaven forbid, if I, or any other teacher, had sent a student to him for misbehaving-----Well, anyway, let's just say that most students did a good job of staying on task and I had very few problems with discipline. Another

thing that I liked about the Catholic High School happened soon

after I started teaching t Undoubtedly my least favorite place to teach was the Buddhist High School. I took the job only because I had befriended the principal of the school. It was on the opposite end of the scale when it came to discipline---there simply was none. The student body was made up mostly, I suppose, of those students would didn't get high enough scores to attend the Public High School or the Semi-Public High School, and who couldn't afford to attend the Catholic High School. It was a rag-tag collection of students from poor families. Chaos reined in the crowded classrooms, and I usually left there wondering why I had ever bothered to show up in the first place. All

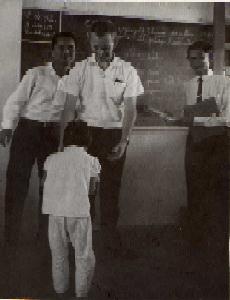

the classrooms in Vietnam were crowded. If I had a class of 30

students, I felt fortunate, because the normal size was, it

seemed, closer to 45 or 50 students. There were few text books.

The teacher wrote notes on the chalkboard, and the students copied

the notes into notebooks. Students must have had volumes of

notebooks before their high school careers were ended. I was a

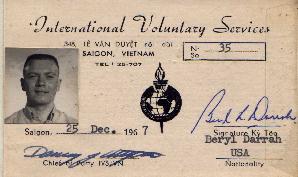

little more lucky, I guess. My organization, the International

Voluntary Services, furnished English text books, under the

sponsorship of the U. S. Information Services and the U.S. Agency

for International Development. But, still, the books did not

belong to the students. I passed them o I suppose the students picked up quite a lot of English by using this method----at least the younger students. My value to the older, more experienced students was to model and correct their pronunciation, sentence structure, etc. And, of course, most of them had never spoken to a "real American" before (including the teachers), so there were often some problems in understanding each other. Like anything else, and like everybody, those who really wanted to learn and improve their English usually had some success. Those who didn't care---well, it was a waste of time for them. People often ask why we spend so much time teaching English to the Vietnamese. I think it was mainly economic. The Unites States presence in South Vietnam was overpowering. We were by the far the largest employer, or at least, the richest employer. The U. S. was hiring thousands of Vietnamese to work in all sorts of positions---interpreters, secretaries, drivers, laborers, servants, clerks, construction workers, etc. And the pay was far superior to what they could earn on the local market. The ability to speak English was a very sellable economic skill in that poor country. Aside from teaching, one of my other projects in Phan Rang was building a public library. A volunteer had been killed some time earlier by (I suppose) the Viet Cong as he was driving his jeep. His parents had donated a sum of money to build a library as a memorial to him. And I was put in charge of making this library a reality. It was a monumental job. There was no library in Phan Rang---and there never had been. Few people had any idea of what a library was. The

details are rather vague in my mind as to how I actually

accomplished the entire task. I do remember that funding was

vastly (and entirely) inadequate to build any sort of a structure,

let alone a public library. But the people in Saigon insisted that

Consequently, most of the material, equipment, and books were scrounged from various sources. A well-known architect donated the plan for the library. Actually, it was just a big open room with some windows and a door. Somewhere we found enough wood to build shelves around the interior of the building. This probably came from some branch of the military, since nobody else would have had access to that much wood, or the money to donate it. Somehow we also came up with some tables which were placed in the middle of the big room. These, of course, were where the local population could sit down and do some leisurely afternoon reading. Oh, yes, the books. What is a library without books? In reality, books were not that difficult to find. The United States Information Agency had hundreds of books which they were eager to give us. The only problem was that these books were so technical in nature that even Americans would have had difficulty reading them. And they were old. Maybe they had taken the old books which were being discarded by Harvard University. To say the least, they were not the kind of books that a typical Vietnamese person with a limited English vocabulary (or even the average American) would read. I looked and begged for weeks trying to find books for the library. I finally located an organization who was willing to donate a very large number of "real" books, books an average Vietnamese living in Phan Rang, South Vietnam, would probably actually read---and would be capable of reading. I was elated; I was overjoyed. But the joy was not long lasting. The people from the headquarter's office had found that this organization had accepted some money from the CIA at one time or other. After that, everything I had worked so hard for went crashing to the ground. They said accepting aid for any organization who had ties from the CIA would compromise our position in Vietnam. What WAS our position in Vietnam? It was something that I never figured out. Whatever it was eventually got us kicked out of the country two or three year later. I am sure the Vietnamese could not have cared less where the money came from---if, by some long shot, they would ever know where it came from. Half of the Vietnamese I worked with were convinced that I worked for the CIA anyway, because I didn't live in an American compound and because I worked with Vietnamese and not Americans. But this was sort of how business was conducted during my stay in Vietnam. Self-defeat by self-righteousness. But. somehow the library was opened, although I am not sure anyone ever actually checked a book out of it. I wasn't around long enough to find out. Sometime before Christmas---It must have been in November---I started feeling very badly. Weak. Sick. I would have to lean on something at school while I was teaching just to be able to stand up. As soon as I finished a class I would go straight home and lie down. I begin to lose my appetite. Actually, I thought that I was simply overworking. I was teaching more than 60 hours a week, aside from trying to get the library up and running. And, I thought it was getting to me. But after a time, I was no longer able to even get out of bed in the morning. It felt as if there was a large metal ball somewhere in my stomach. I lay on the bed almost 24 four hours a day. Our cook would come up to my room and shake her head and tell me that I must eat something. The other guys worked with me were also starting to get a little worried and urged me to go to the doctor. Finally, I was able to drag myself out to my Jeep and drive to the hospital to see an Air Force doctor who worked there. He took a look at my eyes and then took me out on the porch into the sunlight and looked at my back. "You've got hepatitis. Go home and go to bed," he said. I asked what I could do about it. "Nothing. Just keep lying down and get plenty of good food to eat," he replied. "And, no alcohol." "Can I lie on the beach?" I asked. "You can lie on the beach all day long, if you want," he said. Well, that didn't sound too bad, I thought. I stopped at the USAID (United States Agency for International Development) office on my way home and told them that I had hepatitis and that I would not be around for a while. Before I could even finish out the day lounging in bed, the Senior Province Representative had chartered an airplane to "evacuate" me to Saigon. Actually, I think he wanted an excuse to commandeer an airplane so HE could go to Saigon, and I was a very convenient excuse. Well, the trip to Saigon that night would change my life in ways that I never suspected or expected. The

Chief of Party of IVS met me at the airport that night to take me

to the nearby IVS compound. As he was driving back to the house,

he asked me if I would be interested in becoming the next

Associate Chief of Party of Education for Vietnam. I was

flabberg I said good-bye to Phan Rang, to its small town atmosphere, to the friends I had made while I was there, to schools that I had taught in, and to the library that I had just "built". I also had to say good-bye to the long stretches of sandy beach which lay ten minutes away, through the rice paddies and through the ancient ruins of the Cham empire, from our house. The wonderful warm, blue water of the South China Sea where I spend most of my weekends. Returning to Saigon was a sort of dream come true for me. Not only was I to be the new Chief of Education, but I also got to live in Saigon, a city that I loved. For the first month or two---however long it took to get over the hepatitis---I lay around the house in Saigon doing absolutely nothing. As long as I was lying down and was inactive, I felt fine. But even a trip by car to the Post Exchange in the Cholon district of Saigon would completely wear me out. But I spent the time talking to the former Chief of Education, Clarke Davis, and getting to know exactly what the job consisted of. On Christmas Day, I managed to tough it out and go see Bob Hope, who was making one of his marvellous Christmas appearances at Tan Son Nhut Airbase. Seeing one of his Christmas shows (I had seen him earlier while I was in the Army, and would also see him again later.) was worth any discomfort that I may had encountered later. It was great to be among the audience of the thousands of military personnel who so eagerly and gratefully turned out to see him and his troupe perform. On that New Year's Eve I even had a tiny sip of champagne---something that was definitely not recommended. But, again, I suffered no major side effects from it. That began the year of 1967, one of the most exciting years in my young life. My

position as Associate Chief of Party for Education is a difficult

to describe. It involved a lot of dealing with both a lot of

United States government agencies, mostly USAID and USIA (United

States Information Agency) and a lot of private and semi-private

agencies, such as CARE, Red C At the height of manpower in South Vietnam, I think IVS had about 72 teachers located in various provinces around the country---from the Me Kong Delta to the demilitarized zone. A vast majority of them were teaching English in the Vietnamese schools. At one time we had one volunteer teaching some sort of science, but that was an exception. Consequently, I spent about an equal amount of time visiting teachers in the provinces and about half my time in my office in Saigon. It was never clear to me exactly why I spent so much time travelling. Most of the teachers simply did their own thing with little regard to what they should be doing, ought to be doing, or what they were expected to be doing. Life in the "field" was very unstructured, to say the least, with little or no quality control from anybody. But it was interesting and exciting to be able to climb aboard almost any Air America plane or almost any military transport and spend a few days visiting new places and seeing new things. It was also interesting and enjoyable to spend time visiting with the teachers and getting to know them. (During my almost four year in Vietnam, including my military experience, I took over one thousand slides as I travelled about the country. Before I left to return permanently to the U.S.A., I mailed them to my home in Sterling, but unfortunately, and very sadly, none of them ever arrived.) For the most part, these people were different from any other people I had associated with. Some of them were draft resistors and conscientious objectors; some of them were adventurers; some of them were trying to "find themselves", a few of them were even "normal" by my own standards-----but they were all interesting and exceptional and uncommon people. While I was travelling, matters in the office were left in the hands of one of two secretaries who worked for me at different times while I was in Vietnam. My first secretary, whose name was Co Tuc (I think), showed up daily wearing a mini-skirt and considerable make-up. She was outgoing and an extrovert. I think she worked as a singer in a Saigon club at night. My second secretary was the exact opposite. Each day she appeared wearing the traditional Vietnamese pantaloons and long flowing dress. She was quiet and demur and very proper. Each of them was quite efficient and did a good job running the office. I

also had a Vietnamese administrative assistant/interpreter. Phap

was his name, and he sort of acted as my all-round assistant. When

he was around, he always accompanied me when I visited any

Vietnamese government office. He was in charge of translating and

making sense of the vast amount of correspondence I received each

day. He knew immediately what was junk and what needed my

attention. But, as I indicated, he was not always around. Somehow

he managed to juggle at least three different jobs or activities.

He not only worked for me, but he was also a My other Vietnamese employee was Ong Hien, my driver. He was always waiting for me in the morning waiting to drive me through tangled Saigon traffic to my office in central Saigon. While I was working in my office, he spent most of his time playing some sort of Chinese game with the other drivers. But the instant I would appear in the doorway, he dropped everything and came running. He would drive me through the winding, traffic-clogged streets of Saigon to wherever I needed to go. And he would wait patiently until it was time to take me back. Each month, I always bought my ration of cigarettes, five or six cartons, I think, and gave them to him. I am sure he took them and sold them on the black market and made as much or more than he was paid in salary. A couple times a year, I would also give him a bottle of bourbon or vodka. To say this guy was loyal to me is a vast understatement. But it wasn't long before I had mastered the art and intricacies of driving in Saigon. It was all a matter of bluffing and rank---rank of the vehicle I happened to be driving. Tanks obviously always had the right of way, followed by five-ton Army trucks. Then came two-and-a-half ton trucks, followed by Jeeps (That is what I drove.) and other cars, cyclos (open front taxi-like vehicles), motor bikes, bicycles, and last of all, people who had to walk. Although I was terrorized by the traffic at first, it became a game and a challenge. It wasn't long before I became a master at the game of driving. As

a general rule, the people who volunteered as teachers did not

have any training, experience or e The void of any professional standards and quality control led to a blurring and deterioration of the supposed mission of the organization as a neutral "agent of change", as a cadre of young people dedicated to bringing about change on the local level, to a disjointed group of dissidents who were opposed to the U. S. military effort in South Vietnam. There was no demand that they put aside their personal political feelings and do the job they were recruited to do. There was no requirement that they devote their efforts exclusively to working within the local communities and organizations where they had been placed, regardless of the political situation or climate. Many of the volunteers failed to realize that the work they were recruited to do was work that had no political implications----and was work that was important to the people regardless of who controlled the country politically. In any event, members of the organization began to choose sides---those against the war and those in favor of the war. There was very little room left of those who were "neutral", for those who just wanted to do their job and be left alone. The prevailing mood seemed to be "anti-American effort in Vietnam" A manifesto was written by members of the leadership opposing the United States effort in South Vietnam and was signed by several volunteers. A press conference was held with representatives from the TV networks and print media present. IVS officially went of record as opposing the U. S. effort in South Vietnam, and this seemed to mark the end of the effectiveness of the organization insofar as accomplishing any meaningful work within the country. And it also seemed to mark the end of whatever work-related expectations ever existed for the volunteers. To me it was a sad occasion because it destroyed the credibility of the organization with the South Vietnamese people. We were no longer an organization of selfless volunteers who had come thousands of miles to try and teach them a better life---to teach them to live better and to raise their standard of living. We had a different agenda, and this agenda had very little impact on improving the daily life of the Vietnamese villagers. What

impact did this have on my life? I was one of those people who

wanted to be neutral, to do the job that I understood I had been

hired to do. But as time went on, I figured out that there was no

job. Nobody really cared what anybody in the "field" was

doing. The action was in Saigon where After the TET (Chinese New Year celebration) offensive of 1968, the countryside became more insecure, and many volunteers were sent back to the United States. It became obvious that the International Voluntary Services was no longer going to be an effective organization in South Vietnam and that it no longer would play any role in bringing about meaningful change on the local level which would improve the quality of life for the Vietnamese people. After I had returned to the United States and had returned to the teaching profession, I just happened to spot a short news story in the newspaper saying that the International Voluntary Services had been expelled from Vietnam. Somehow, I was not surprised. Even more than thirty-five years later, I look back upon my experience in South Vietnam fondly and with nostalgia----especially the time I spent in Saigon. All of us Associate Chiefs of Party were young and ambitious. We used to sit around at night, drinking Filipino or Vietnamese beer and marvel about the opportunity which had been handed to us. We were in an exciting place at an exciting time. We met political figures who visited our headquarters compound. People like Ted Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge. Lodge's grand daughter worked for IVS, so he became a rather familiar face to us all. I gave English lessons to the Archbishop of Vietnam (and even got Christmas cards from him for a couple years after I returned home). I taught the brother of the National Police Chief. I sat on the same reviewing stand as the President and Vice President of South Vietnam. I ate lunch with the President once. I met and worked with several ministers in the South Vietnamese government, including the Minister of Education, the Minister of Agriculture and the Minister of Youth Affairs (or something like that). I taught English for a time at both the University of Saigon and the Buddhist University. I met important Buddhist leaders and dissidents (who seemed so polite and mild). I attended the inauguration of President Thieu----and I remember seeing the parade with Vice President Humphrey's car surrounded by dozens of Mafia-type body guards---and President Thieu riding in an open Jeep, with no protection whatsoever, smiling and waving to the crowd. I

also recall fondly the countless hours I spent wandering through

the streets of Saigon, with its c It all brings back good memories. Even the not so good memories have been dulled (or sharpened) by the passing years. I can still hear the concussive explosions of the mortars as they landed less than a block from our emergency residence in central Saigon. I remember sleeping on the floor, with the bed between me and the window on nights when there seemed to be a lot of gunfire in the outskirts of Saigon. I can remember the eerie reflections caused by the flares which lit up the Saigon night as they leisurely floated to the earth. I can remember standing on the roof-top patio any night of the week and watching our helicopters and airplanes send a steady stream of bullets from their Gattling guns toward suspected VC hiding somewhere in the Chinese sector, or seeing our F-1 or F-4 jet fighters make pass after pass of diving bombing raids aimed toward these same suspected VC soldiers hidden somewhere below. I still have a piece of shrapnel from a bomb or mortar which I dug out of my bedroom window after returning home from one of our extended evacuation stays at our hotel. I also remember the time when fighting erupted in our backyard one morning. And that also reminds me of a basic truth I learned about people as a result of that incident. As I mentioned earlier, many of the young men who volunteered for our organization were conscientious objectors---people who opposed war on moral or religious grounds. On many occasions, in my more naive days, I would argue with the guys, asking such questions as, "What would you do if someone had a gun and was going to shoot you?" Reply: "I would try to talk them out of it, or reason with them." Question: "What would you do if someone was about to kill a member of your family?" Reply: " I would try to talk them out of it or reason with them." Question: What would you do if a foreign country attacked our country?" Reply: "I would not fight and kill other human beings." Well,

as you can see, this kind of discussion is rather pointless and

silly. But, like I said, I was naive and I had never encountered

people like this before (or since.) Getting back to the story.

That morning, suddenly gunfire erupted somewhere in our backyard,

followed by more gunfire. It began to get closer, until it was

apparent that fighting was taking place right outside our house.

Somewhere in the house, there were four rifles (something I was

unaware of until that moment.) I had already served three years

active duty in the U. S. Army, one of which was in Vietnam. During

By this time we were all huddled upstairs, lying prostrate on the floor, with our conscientious objectors pointing the rifles toward the door. The battle soon subsided, and an air of calm returned. We were not the intended targets of the skirmish. It was a brief battle between the South Vietnamese and perhaps some suspected Viet Cong. Just one other story before I sort of let Vietnam fade into the past. One morning there was a loud knock on my bedroom door. When I opened it, I expected to find one of my teachers standing there asking me for an early morning ride to the airport. Instead it was one of the female teachers who was stationed in Saigon. "Wake up, Beryl. Something bad is happening. The rockets and mortars are different than they usually are." "It's nothing to worry about. The VC do this every morning," I told her. "Go back to bed and go to sleep." "No, it is different this time. Saigon is being attacked." I got up and dressed quickly and walked under the covered passageway to the adjacent building where the dining room was located. As I walked into the kitchen, the mood was somber and strained. Indeed, the Viet Cong has launched coordinated attacks all over South Vietnam that night. Our cooks were worried. The bread vendors had not showed up to sell their bread that morning. Traffic past our house, which was located on a main street leading to Tan Son Nhut Airbase, was lighter than usual. An unusual number of tanks and military vehicles were in the streets. Soon a military curfew was imposed upon the city. The street in front of our house was blocked off. The night before I stood with a friend of mine on our second story patio listening to the deafening sound of fireworks as the Vietnamese celebrated the Chinese New Year. As the sky lit up with fireworks mingled among the flares and the ever-present red lines of tracer bullets from the U.S. fighter jets, I turned to my friend and said, "This would be a great night for the Viet Cong to launch an attack." ---Never suspecting it would happen. In fact, everyone suspected the exact opposite. Most people believed that both sides would cease the fighting in order to observe and celebrate TET, the Chinese New Year. After all, the Vietnamese are very tradition oriented. We

spent a day quarantined in our compound. It was a long tense day.

We spent a lot of time watching the soldiers patrolling in front

of our house, which was so close to the air base. Someone had made

a big bowl of punch to be used in a New Year's party, but The next day we were allowed to leave our compound and drive toward Saigon, but not toward the airbase, just a few hundred meters away. The city was still under heavy military surveillance. But I eventually made my way to the house of my administrative assistant to celebrate the birthday of his young son. Soon announcements began to flow out over the Armed Forces Radio Network telling people to stay off the streets, that the situation was dangerous. We decided that I would simply stay at his house until conditions became somewhat more stable, if not safe. I really had no way to tell anybody at our house where I was and what I was doing. Somehow and somewhere in the confusion, I was reported missing. This report was somehow reported to my family back home and to the newspaper. It gave my family some anxious moments, until I was "found" the next day. But the newspaper story gave me a good souvenir when I arrived home some months later. Later Phap, my administrative assistant, told me that the barber who had cut his father's hair for the past several years, turned out to be one of the VC leaders of the raid on Saigon----one of those sad indications of a civil war. You never know for sure who the enemy is. Although

TET was suppose to be a major victory for South Vietnam and the

United States, it was probably the turning point in the war. The

point at which public opinion in the U. S. A. began to turn

against our involvement. It also seemed to be the point in time

when security began to deteriorate not only in the outlying

provinces, but also in Saigon. It marked a definite change in our

organization---a darker mood, a more militant anti-U.S. and

anti-war mood. The mood that would u It also affected my attitude about remaining in South Vietnam. I began to feel that I could no longer be effective, because there was no longer any need for a Chief of Education. In fact, there was very little actual work still being performed by our volunteers anywhere in the country. I also began to question whether I wanted to continue to risk my life and safety for a cause which I was no longer committed. In the end, all these factors began to point me in the direction of home. |

eneral.

I visited Prosperity School, the last school in which I taught

before joining the army. The people I used to work with were happy

to see me, but the fact that I had just returned from Vietnam

meant next to nothing to them. Vietnam had not yet become a

household word. Vietnam still had not become a dirty word.

eneral.

I visited Prosperity School, the last school in which I taught

before joining the army. The people I used to work with were happy

to see me, but the fact that I had just returned from Vietnam

meant next to nothing to them. Vietnam had not yet become a

household word. Vietnam still had not become a dirty word.

entrate

on what my supervising teacher was doing. He was a former college

classmate of mine and had married my neighbor girl. Not being a

very inspiring teacher, it was often difficult to keep my mind on

watching his example. This particular day I was leafing idly

through a Redbook magazine when I happened to come across an

article about the International Voluntary Services. This jolted me

fully awake and caught my attention. This, I knew, was going to by

my ticket back to South Vietnam. After filling some application

forms and going through a routine interview, I was told that I had

been accepted as a volunteer teacher in South Vietnam.

entrate

on what my supervising teacher was doing. He was a former college

classmate of mine and had married my neighbor girl. Not being a

very inspiring teacher, it was often difficult to keep my mind on

watching his example. This particular day I was leafing idly

through a Redbook magazine when I happened to come across an

article about the International Voluntary Services. This jolted me

fully awake and caught my attention. This, I knew, was going to by

my ticket back to South Vietnam. After filling some application

forms and going through a routine interview, I was told that I had

been accepted as a volunteer teacher in South Vietnam.

retty

much a chicken; but to him a chicken was a CHICKEN. Today, I think

he has a PhD in poultry science and he is probably making a lot of

money at it. I am pretty sure that he was working with the local

farmers doing other useful things, too, insofar as introducing new

plants, obtaining better feed for pigs and livestock.

retty

much a chicken; but to him a chicken was a CHICKEN. Today, I think

he has a PhD in poultry science and he is probably making a lot of

money at it. I am pretty sure that he was working with the local

farmers doing other useful things, too, insofar as introducing new

plants, obtaining better feed for pigs and livestock.

point

when I thought if I saw another grain of rice, I would undoubtedly

go insane. This was one of the cultural adjustments which I had to

make in those early days of living more or less on the Vietnamese

economy. I learned to love rice as the months went by, and it was

probably the food that I craved most after I returned to the U. S.

two and a half years later.

point

when I thought if I saw another grain of rice, I would undoubtedly

go insane. This was one of the cultural adjustments which I had to

make in those early days of living more or less on the Vietnamese

economy. I learned to love rice as the months went by, and it was

probably the food that I craved most after I returned to the U. S.

two and a half years later.

me

to set up a schedule and create my own job. Our regional director

introduced me to the principal of the public high school. But word

in a small town spreads fast, even in Vietnam, and soon I was

being contacted by representatives of every school in town wanting

me to teach in their school---the Catholic High School, the

Buddhist High School and a school called the Semi-Public High

School.

me

to set up a schedule and create my own job. Our regional director

introduced me to the principal of the public high school. But word

in a small town spreads fast, even in Vietnam, and soon I was

being contacted by representatives of every school in town wanting

me to teach in their school---the Catholic High School, the

Buddhist High School and a school called the Semi-Public High

School.  here.

It was during one of my first breaks when we teachers were sitting

in the faculty room. One of the teachers reached into a cabinet

and pulled out a bottle of bourbon, and they all proceeded to have

a quick drink. I was rather startled, but not wanting to offend my

colleagues, I quickly accepted when the bottle made its way to me.

here.

It was during one of my first breaks when we teachers were sitting

in the faculty room. One of the teachers reached into a cabinet

and pulled out a bottle of bourbon, and they all proceeded to have

a quick drink. I was rather startled, but not wanting to offend my

colleagues, I quickly accepted when the bottle made its way to me.

ut

and collected them each class. And the method of teaching was the

"repeat after me" method. Which was OK, I guess. The

books used sentence patterns, such as, "This is a _____",

and I would teach as many objects as possible to fill in that

blank. Or, perhaps, the sentence may have started, "I am

going to the _____" Or, "I like to _____ in my spare

time."

ut

and collected them each class. And the method of teaching was the

"repeat after me" method. Which was OK, I guess. The

books used sentence patterns, such as, "This is a _____",

and I would teach as many objects as possible to fill in that

blank. Or, perhaps, the sentence may have started, "I am

going to the _____" Or, "I like to _____ in my spare

time."

the

project be completed.

the

project be completed.

asted,

as well as flattered. It was something that I never expected---but

something that I certainly could not turn down.

asted,

as well as flattered. It was something that I never expected---but

something that I certainly could not turn down.

ross,

Catholic Relief, etc. Coordinating and conferring with the

Vietnamese government, which was subject to change with each coup

de tat was also a major part of my job. Actually, I am rather sure

that they could have not cared less what we did just so long as we

kept the money rolling in and it didn't cost them anything.

ross,

Catholic Relief, etc. Coordinating and conferring with the

Vietnamese government, which was subject to change with each coup

de tat was also a major part of my job. Actually, I am rather sure

that they could have not cared less what we did just so long as we

kept the money rolling in and it didn't cost them anything.  lieutenant

in the South Vietnamese Army and a medical student at Saigon

University. Somehow, I think this young man had some good

connections somewhere. But he was a pleasant, funny guy, very

bright and resourceful. He was usually the first person I

consulted when I wanted to find out something or if I needed

something or if I wanted something done.

lieutenant

in the South Vietnamese Army and a medical student at Saigon

University. Somehow, I think this young man had some good

connections somewhere. But he was a pleasant, funny guy, very

bright and resourceful. He was usually the first person I

consulted when I wanted to find out something or if I needed

something or if I wanted something done. volunteers

were encouraged to come and debate and attack the U. S.

involvement in South Vietnam. Any standards or expectation which

may have existed had evaporated. And as one of those who refused

to join in the debates, the monologues, the "white papers",

the anti-war discussions, I began to find myself more and more

isolated and frustrated.

volunteers

were encouraged to come and debate and attack the U. S.

involvement in South Vietnam. Any standards or expectation which

may have existed had evaporated. And as one of those who refused

to join in the debates, the monologues, the "white papers",

the anti-war discussions, I began to find myself more and more

isolated and frustrated.

logged

streets and sidewalks. The flower markets, the fish markets, the

markets with live animals, and markets with a myriad of black

market merchandise. I remember browsing through the local art

galleries which displayed not the "old masters", but the

latest works of its native artists---street scenes, war scenes,

rice paddies and water buffalo. The Presidential Palace was a

familiar sight. I drove past it each day as I drove to work and

then again as I returned home. The same thing was also true of the

old Gia Long Palace, where the Diem brothers ruled. The United

States Embassy, the old Saigon City Hall, the National Assembly

(which was turned into an art exhibition center while I was

there). I look back to the times I sat and sipped coffee on

veranda of the old Continental Hotel or strolled along the Saigon

water front.

logged

streets and sidewalks. The flower markets, the fish markets, the

markets with live animals, and markets with a myriad of black

market merchandise. I remember browsing through the local art

galleries which displayed not the "old masters", but the

latest works of its native artists---street scenes, war scenes,

rice paddies and water buffalo. The Presidential Palace was a

familiar sight. I drove past it each day as I drove to work and

then again as I returned home. The same thing was also true of the

old Gia Long Palace, where the Diem brothers ruled. The United

States Embassy, the old Saigon City Hall, the National Assembly

(which was turned into an art exhibition center while I was

there). I look back to the times I sat and sipped coffee on

veranda of the old Continental Hotel or strolled along the Saigon

water front. this

time I had earned Expert Marksman Badges on four separate

occasions. And supposedly I had been trained to kill. But, do you

think I was given one of these rifles? Not on your life. There was

a mad scramble by the so-called conscientious objectors---the guys

who would never kill anyone under any circumstances---for the

weapons. Does a person really think he will not defend his own

life when it is in imminent danger? You bet they will. All the

theory, all the rationalization, all of the high sounding

intentions in the world sort of wave good-bye when it comes down

the choice, "Your life or mine."

this

time I had earned Expert Marksman Badges on four separate

occasions. And supposedly I had been trained to kill. But, do you

think I was given one of these rifles? Not on your life. There was

a mad scramble by the so-called conscientious objectors---the guys

who would never kill anyone under any circumstances---for the

weapons. Does a person really think he will not defend his own

life when it is in imminent danger? You bet they will. All the

theory, all the rationalization, all of the high sounding

intentions in the world sort of wave good-bye when it comes down

the choice, "Your life or mine."

it went largely untasted. Nobody felt like drinking.

it went largely untasted. Nobody felt like drinking.